This series of posts covering the topic of the unsavoury origins of the BBC is re-posted by kind permission of The Occidental Observer, where the original article can be found in full at this link. The third of four parts of this series covering the murky origins of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

John Reith

Isaacs’ importance in the founding of the BBC only began to be publicised after the meeting transcripts emerged in 2018. Until then, historians appear to have universally attributed its creation and its ethos to the Post Office and then to John Reith, the company’s first general manager. 49 Reith’s appointment was, in fact, a further manifestation of the power of the patent-rich ‘first group’ at the May meeting: Marconi led by Isaacs, GEC led by Hirsch and British Thomson-Houston acting for the American Morgan-controlled General Electric, part-owner and partner of David Sarnoff’s RCA. Contrary to myth (and the BBC’s own website), it was Sarnoff, not Reith, who first declared that the mission of public broadcasters was to “inform, educate and entertain”.

Reith, responding to an advertisement, applied to become general manager of the new Company (the British Broadcasting Corporation came later) in October 1922, with the Company due to begin operating at the start of 1923. Though he appears to have had little involvement in politics before this time, he had spent some of the previous months as an aide-de-camp to William Bull MP, a Tory supporter of Austen Chamberlain (brother of Neville and son of Joseph), who was, at that time, working for a continuation of the existing coalition government under David Lloyd George, Liberal Prime Minister since 1916. Between applying for the BBC job and being interviewed, Reith was introduced privately to Lloyd George. 50 The coalition lost power in the election of November.

Reith appears to have been chosen for the job before his interview in December. According to Asa Briggs:

“… unfortunately there are no surviving records in the BBC archives or elsewhere of what was happening behind the scenes. There is not even a surviving short list of the six people seriously considered for what was to be a strategic post in British twentieth-century history.”

Kellaway was said to have been considered but “moved instead after the Coalition Government’s defeat to the more lucrative post of Managing Director of the Marconi Company.” 51 When Isaacs died in 1925, Kellaway replaced him as Marconi’s member of the BBC board.

Reith was interviewed by his former employer, William Bull MP, who was a director of the British branch of Siemens, and William Noble, a director at Hirsch’s GEC. According to Ian McIntyre,

“Noble greeted him ‘with the cordiality of an old friend’. The previous night, Reith had ‘put all before God’, but that was the limit of his preparation:

“ ‘They didn’t ask me many questions and some they did I didn’t know the meaning of. The fact is I hadn’t the remotest idea as to what broadcasting was. I hadn’t troubled to find out. If I had tried I should probably have found difficulty in discovering anyone who knew’.” 52

As Briggs says, Reith was “ignorant of broadcasting”. 53 He continues:

“The following day Noble, who at the end of the interview ‘almost winked as if to say it was all right’, telephoned Reith to tell him that the Board was unanimous in offering him the post. Reith had asked for a salary of £2,000, but Isaacs insisted on seeing Reith before he would agree even to a lower figure of £1,750. At this second interview, when the dominating figure in the talks leading up to the incorporation of the BBC met for the first time the man who was to be the dominating figure in the events which followed its foundation, all went off well and Reith was approved. In his formal letter of acceptance he noted that the General Manager would ‘have the full control of the company and its staff’, and would be ‘responsible to the Directors’.” 54

According to Tim Wu, “…his selection was something of a mystery, even to him”. 55 Reith attributed it to the divine:

“He believed that he was called to the BBC not by Bull or Noble (who chaired the committee which interviewed him) but by Providence. ‘I am properly grateful to God for His goodness in this matter’, he wrote in his diary.” 56

With due respect to Providence, there are reasons to suspect that Reith’s appointment owed more to material factors, specifically the interests of GEC, BHT and Marconi and their directors. 57 Reith certainly accorded closely with those interests. Better still for them, he added to the covetous demands of the Company’s directors for safe and protected revenues his own arguments for the BBC in ‘high’ terms of quality and public service. He and the board, with Isaacs and Noble foremost, also intoned the myths Brown had brought across the ocean and devised their own. 58, 59

Robbery

The BBC board made no secret of its desire to force higher prices on listeners. In the autumn of 1922, soon after the BBC was announced and before it began operating, firms began to import radio components and market them partly assembled with instructions for completion. They “could thereby avoid buying the more expensive British-made sets which bore the BBC mark” and “avoided the necessity of paying royalty to the BBC on the purchase price of the apparatus—they might even evade paying royalty to the Marconi Company”.

Briggs’ particular mention of Marconi suggests that they received royalties that even the other big manufacturers did not. As “the market was flooded with foreign-made parts … the revenue of the BBC both from royalties and licences was far smaller than had been anticipated when the Big Six went into combination. The estimated 200,000 licence-holders were proving extremely difficult to recruit.” 60 The BBC board issued a statement castigating “importers” who were “prepared to reap where others have sown”, and who would “rob the British radio industry of its protection and … jeopardize good standards of broadcasting”. 61

The board simultaneously asserted that “[t]he initiative which had led to the formation of the BBC had come from the Post Office”. William Noble, speaking at the Sykes Committee in Parliament in 1923, asserted that “It was the desire of the Post Office that we should have one company and one company only… and we fell in with the view.” 62 Nobody knew better than the authors of these statements that they inverted the truth. 63 As we have seen, the Post Office was prepared to issue multiple licences while Marconi’s patent power enabled Isaacs to ensure that there would be only one.

“Sportsmanship”

After Kellaway joined Marconi, less than two months after leaving his position as Postmaster-General, his successors were reluctant to enforce the BBC’s demands, contrary to Noble’s claim that the scheme was “the desire” of the Post Office. As the licence fee was the means by which listeners were compelled to buy equipment from the member companies of the BBC, the board lobbied for its enforcement. They complained in a meeting with Brown in January 1923 that no prosecutions were being made and that “police action was necessary”. 64 Neville Chamberlain, the Postmaster-General until March, was “entirely unhelpful” and “scoffed” at the idea of enforcement when Reith and Noble lobbied him informally in February. 65 Chamberlain’s successor, William Joynson-Hicks, was even less congenial at first.

In Parliament, William Bull repeated Noble’s assertion that Isaacs and Hirsch’s scheme had been the Post Office’s idea. Joynson-Hicks appears to have known better, referring to the negotiations of the previous year, and attributed the agreement to Kellaway personally; Kellaway, writing in The Times, threw the potato to Chamberlain who threw it back, and Kellaway dissembled to evade attribution for a scheme he had carefully framed as Postmaster-General and of which he was, by then as a director of Marconi, a leading beneficiary. 66,67

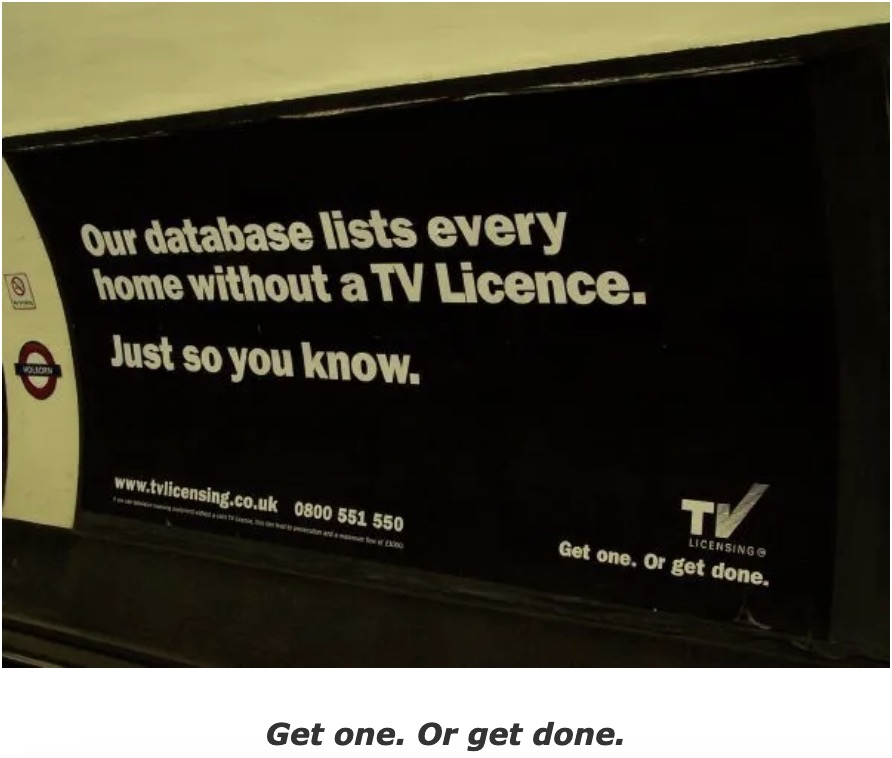

Joynson-Hicks, struggling to adjudicate, had a committee appointed with Frederick Sykes, son-in-law of the Prime Minister, Andrew Bonar Law, in the chair. It began hearings in May, on which sat John Reith and to which the BBC board and Reith argued that “it was ‘one of the fundamental essentials of the Agreement’ that there should be no evasion” and that “the only satisfactory way of preventing evasion was to prosecute people who did not possess wireless licences”. Detection was often possible thanks to the “prominent outdoor aerials”. In Briggs’ words, “Although it might have been difficult to prosecute all offenders, the psychological and moral effect of prosecuting a few known offenders would have been very great.” 68

By the time the committee reported, another new Postmaster-General, Laming Worthington-Evans, had been won over by Reith in private and the licence fee began to be enforced in earnest. “Post Office motor vans” were sent out “not to detect but to intimidate” the “scroungers”, “eavesdroppers” and “pirates” who showed a dearth of “sportsmanship” by using equipment lacking the required BBC marque. 69 The public began to be habituated to obey the broadcasting monopoly and its directors.

Footnotes

49 The BBC itself published a history omitting mention of Isaacs or Sarnoff.

50 McIntyre, p116

51 Briggs, Birth, p137. Kellaway’s move to Marconi was mentioned in Parliament.

52 McIntyre, p116

53 Briggs, BBC, p43

54 Briggs, BBC, p45

55 The Master Switch, Tim Wu, 2011, chapter 4

56 Briggs, BBC, p44

57 The other directors of the BBC are listed here.

58 William Noble was remarkably supportive of a scheme he claimed had been imposed on his firm by the Post Office.

59 “ ‘BBC programmes are often rendered farcical’, Noble complained [in January 1923], ‘by interference caused by amateurs tuning up and causing disturbance and by the transmission of messages’.” Briggs, Birth, p148. This appears to be a fabrication.

60 Briggs, Birth, p146-7

61 Briggs, Birth, p160-1

62 Briggs, Birth, p180-2

63 Briggs, Birth, p160-1

64 Police action “should be preceded by the publication of an official notice in the newspapers stating that the Postmaster General was aware that many unlicensed sets were being used and that their owners would immediately be prosecuted.” Briggs, Birth, p147

65 Briggs, Birth, p149

66 “Sir William Bull, who was the only director of the BBC who was also a member of parliament, reminded Joynson-Hicks that it had been the Post Office which had suggested this arrangement. The Postmaster-General equivocated, saying that it had been ‘the result of numerous negotiations between the Broadcasting Company and the then Postmaster-General.’” Briggs, Birth, p161-2

67 “Sir W. Joynson Hicks (who had become Postmaster General after Mr. Neville Chamberlain) said in the House of Commons that Mr. Kellaway had made the agreement. Mr. Kellaway thereupon wrote to The Times saying that the agreement was made by Mr. Chamberlain three months after he had left the Post Office. Mr. Chamberlain replied in a speech that “this was a transparent quibble. He had only put his name to it and not altered a word”. Mr. Kellaway then wrote another letter to The Times in which he claimed that “this involved the most startling evasion of responsibility”. See The Times for April 21st, 23rd, 24th and 26th, 1923.” Coase, Origins, p201, note 4

68 Briggs, Birth, p166

69 Briggs, Birth, p192, 220

For the remaining parts of this study, click here for Part 1, click here for Part 2, and click here for Part 4.